A Practical Guide for New & Intermediate Traders

If the forex market were a nightclub, the major currency pairs are the VIPs hogging all the attention: EUR/USD under the spotlight, USD/JPY sipping champagne, GBP/USD refusing to leave. But head deeper just past the bouncers guarding the dollar-based dance floor - and you’ll find the hidden rooms where exciting things happen - trading the minor pairs.

These “less famous” currency pairs may not always trend on social media or get flashy headlines, but they offer unique opportunities for traders who know where to look, along with a bit more personality (and volatility) than their polished major cousins.

Let’s look why expanding beyond major pairs could be one of the smartest moves you make on your trading journey.

Quick Refresher: What Makes the Forex Market Special?

The forex market is the largest market on Earth - averaging $5+ trillion in daily volume. That’s around 25 time larger than the worldwide stock market’s average day. With that much money zipping around the planet 24/5, even the smaller lanes still carry big traffic.

Currencies are influenced by:

● Supply & demand

● Central bank decisions

● Economic data

● Credit ratings and capital flows

● Trade relationships

● Politics & geopolitics

● Market sentiment (a.k.a. trader mood swings)

Major pairs follow these drivers closely - but minor pairs often react more dramatically, creating potential strategic money-making opportunities.

What Exactly Are “Minor Pairs”?

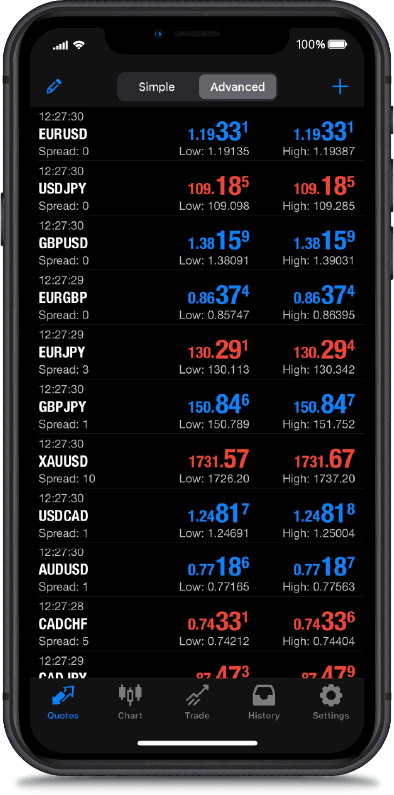

Minor pairs (sometimes called cross-currency pairs) do not include the US dollar.

Examples include:

● EUR/GBP

● EUR/JPY

● GBP/JPY

Then there are those involving emerging or commodity-linked economies, often grouped as “exotic pairs” - even though there’s nothing exotic about a central bank panicking during an inflation spike:

● USD/MXN (US Dollar / Mexican Peso)

● USD/ZAR (US Dollar / South African Rand)

● AUD/NZD (Australia vs. New Zealand - a kangaroo vs. a kiwi showdown)

● AUD/CAD (Mining vs. Oil: the commodity cage match)

These are the stars of trading minor pairs - offering exciting setups for hungry forex traders.

Why Bother With Minor Pairs?

Here’s where things become interesting…

1. They React More to Local News

Major currencies can shrug things off. Minor currencies? Not so chill.

For example:

● Election surprises

● Trade policy arguments

● Leadership changes

● Credit downgrade whispers

These can send minor pairs flying like a cat who’s seen a cucumber. That volatility = opportunity if you understand the context of the news releases.

2. Potential Mispricing

Since fewer traders and institutions track these pairs closely…

● Inefficiencies can appear

● Savvy traders can take advantage

3. Carry Trade Benefits

Some minor pairs provide higher interest rate differentials, which can pay traders overnight funding profits if positioned correctly. More on that further on…

4. Diversification

If major pairs get dull or choppy, minor pairs provide alternatives - especially when you want exposure to certain economies or commodities.

Current Global Themes Driving Minor Pair Movement

Time to connect this to right-now events

1. Mexico: Tariffs, Elections & Trading Policy

Mexico has been strengthening trade leverage by considering tariffs of up to 50% on strategic imports. The peso - already a favourite for carry trades - is reacting sharply as investors speculate how US-Mexico relations evolve.

Pairs to watch: USD/MXN, EUR/MXN

2. South Africa: Fiscal Uncertainty & Government Transition

With South Africa shifting into a new coalition government structure, confidence can shift rapidly - and the rand tends to express those emotions loudly.

Pair to watch: USD/ZAR

3. Asia: Central Bank Divergences

Japan remains ultra-loose with monetary policy compared to Australia or New Zealand - making yen crosses a carry-trade playground.

Pairs to watch: AUD/JPY, NZD/JPY, EUR/JPY

4. Emerging Markets: Risk-On vs. Risk-Off

When global sentiment is upbeat (risk-on), money flows into higher-yielding markets. When recession fears spike (risk-off), capital sprints back into USD or JPY for “safety.” These dynamic movements can hit minor pairs first and the hardest.

Commodity-Linked Minor Pairs: Trading Resources, Indirectly

A cool perk of trading minor pairs: You can trade commodity exposure without touching commodities directly.

Currency

Major Commodity Influence

Example Minor Pair

AUD

Iron ore & industrial metals

AUD/JPY

NZD

Agriculture (milk & dairy exports)

AUD/NZD

CAD

Crude oil & timber

AUD/CAD

So, if you think iron ore is in demand, then……

● NZD might outperform AUD - Possibly short (sell) AUD/NZD

If oil spikes on Middle East supply risk?

● CAD may strengthen vs AUD – Sell (sell) AUD/CAD

Commodity exposure = more strategic angles = more opportunity for trading minor pairs.

Carry Trading: The Classic Minor Pair Power Move

Time for the famous - and sometimes infamous - strategy…

What’s a carry trade?

● Borrow or sell a low-interest currency

● Buy a high-interest currency

● Collect the interest difference (the “carry”)

The yen (JPY) has been a favourite funding currency thanks to super-low rates.

Popular examples:

● NZD/JPY

● AUD/JPY

And when emerging markets offer juicy rates?

● USD/MXN

● USD/TRY (Turkey… not for the faint-hearted!)

The danger?

Exchange rate moves can eat your carry gains - or worse. A sudden central bank surprise… and boom, it gets messy!

The Risks: Because We Don’t Trade With Blinders On

Trading minors = more reward potential because the risks are bigger.

Here’s what makes minor pairs the wild cards of forex:

● Higher volatility

● Wider spreads

● News sensitivity

● Liquidity drops during off-hours

● Geo-political shock potential

● Large stop hunts in thin markets

This is where risk management is your best friend:

● Never risk what you can’t lose

● Set stops beyond expected noise

● Reduce position size

● Monitor swap/overnight costs

● Understand the local economy dynamics

Minor pairs reward informed, patient, disciplined traders - not adrenaline addicts.

How to Research Minor Pairs Like a Pro

Here’s your mini roadmap:

● Central bank direction: Interest rates drive everything

● Trade relationships: Who sells what to whom?

● Political calendar: Elections, referendums, scandals (those arrive often)

● Credit ratings: Downgrades = currency tantrums

● Commodity price charts: AUD, NZD, CAD in particular

● Market mood: Are investors seeking safety or risk?

Taking the time to understand one minor pair deeply beats trading 10 majors blindly.

Why Minor Pairs Belong in Your Trading Toolkit

Here’s the bottom line:

● Fresh opportunities when the majors’ pairs are stale

● Mispricing potential due to lower coverage

● Educational value - you learn real global economics

● Chance to diversify trading styles

● Better alignment with geopolitical themes

Even if you only add one or two minor pairs to your weekly rotation… That’s already a strategic edge over traders who ignore them entirely.

Final Thoughts: Go Where Others Aren’t Looking

Major pairs are important - they are the backbone of global FX. But when everyone crowds into the same EUR/USD trade, sometimes the smarter move is simply to…

Walk down the hall. Open the door labelled USD/MXN, Enter If You Dare! And discover a more interesting story.

Minor pairs are where the global world - politics, trade, commodities, human drama - express themselves loudest.

If you stay informed, manage risk, and bring an analytical mindset, then: Trading minor pairs could be the difference between a limited trading toolbox…and a portfolio full of new possibilities.