Government bonds are part of the long list of items that play almost no part in the lives of the average person, and yet behind the scenes they are crucial. Not only are they critical for investors, particularly the bigger investments firms, but they also shape the economic landscape of their country of issuance as well as play a pivotal role in the way a government raises funds.

So what is a bond? In the simplest terms, a bond is an IOU issued by the government. The government periodically puts bonds up for sale, with different interest rates and different maturity dates, varying from just a few months up to several decades. Investors are then free to purchase these bonds, at which point they become tradeable assets in an open market.

The exact name of this type of financial instrument differs depending on the length of time to maturity, as well as the country in which it was issued. In many parts of the English-speaking world, they are instead referred to as “gilts”. For the purpose of this article, we will employ the term “bond” as a catchall term for all such government-issued debt securities.

For longer-term bonds, the holder periodically earns a reward in the form of an interest payment, usually called the coupon. Once the bond reaches maturity, the government pays the face value back to the redeemer - typically $1000 for US bonds. Up until that point, bonds are freely tradeable and valued at whatever price the market deems appropriate.

It is important to properly define yield in the context of the bond market, because the definition differs somewhat from comparable investments. For a bond, two factors define the yield: the interest payments (coupon payments), and the spread between the purchase price and the face value of the bond.

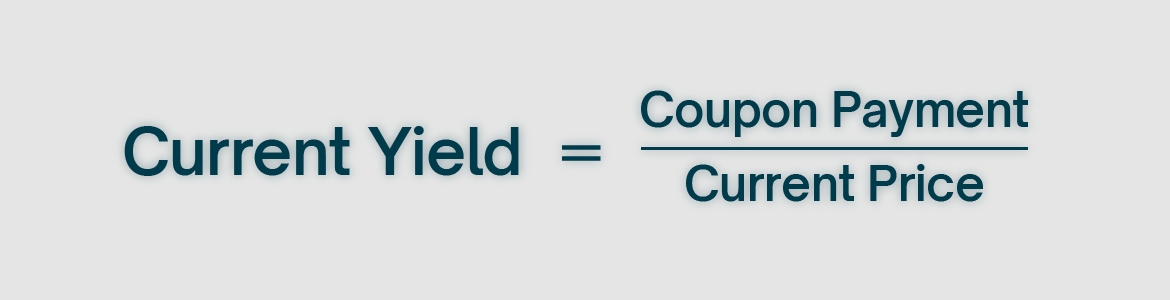

The simplest calculation, called the current yield, is as follows:

We can see from the above formula that the yield and the price are inversely correlated, meaning that if the price of the bond were to fall, then its yield would increase. Indeed, if an investor were to purchase a $1000 bond with a 5% coupon rate (meaning a $50 payment) at face value, the current yield would also be 5%. However, if an investor were to purchase the same bond at a discounted price of $800, then the current yield would increase to 6.25%. Important to keep in mind when reading financial news relating to falling/rising yields.

Another, and more perhaps more useful calculation, is the yield-to-maturity rate, which is the total return on investment made on the bond, assuming it is held until the maturity date. Such a calculation also assumes all coupon payments are reinvested at the same rate as the bond’s current rate, making it relatively difficult to calculate and certainly falling outside of the scope of this article. As we mentioned before, only longer-term bonds typically earn a coupon, meaning that the yield on shorter-term bonds is entirely defined by the spread between the purchase price and the face value.

For investors, the salient point about a bond is that it is a financial investment guaranteed by the government, and as such is considered the safest possible investment one could make. After all, if the government is no longer in a position to financially honour the bonds it issues, the investor will probably have much bigger problems to worry about than their portfolio.

For governments, bonds are an important part of how they fund their activities. By selling bonds, the country is essentially raising money, with the promise to pay back that money with interest further down the line. They are one of the primary tools a government uses to raise funds.

They also play another, essential role. Traditionally, a country would manipulate the strength of its currency by controlling the money supply. The more money in circulation, the weaker that money tends to be, and vice-versa. To increase the money supply, the central bank of that country would purchase government bonds, thereby injecting money into the system. Conversely, by selling those bonds, the central bank takes all that money back, reducing the supply. This is the mechanism by which a country could increase and decrease the money supply, and by doing so manipulate the relative strength of its currency.

The post-2008 modern financial era differs somewhat from this framework, but the buying and selling of bonds continues to be an important steering tool for monetary policy. To understand how, we need to look at something called the yield curve, which we will cover in part II of this article.

Advertencia de riesgos : Productos derivados del trading y productos potenciados poseen un nivel más alto de riesgo.

ABRIR CUENTA