Government bonds are part of the long list of items that play almost no part in the lives of the average person, and yet behind the scenes they are crucial. Not only are they critical for investors, particularly the bigger investments firms, but they also shape the economic landscape of their country of issuance as well as play a pivotal role in the way a government raises funds.

So what is a bond? In the simplest terms, a bond is an IOU issued by the government. The government periodically puts bonds up for sale, with different interest rates and different maturity dates, varying from just a few months up to several decades. Investors are then free to purchase these bonds, at which point they become tradeable assets in an open market.

The exact name of this type of financial instrument differs depending on the length of time to maturity, as well as the country in which it was issued. In many parts of the English-speaking world, they are instead referred to as “gilts”. For the purpose of this article, we will employ the term “bond” as a catchall term for all such government-issued debt securities.

For longer-term bonds, the holder periodically earns a reward in the form of an interest payment, usually called the coupon. Once the bond reaches maturity, the government pays the face value back to the redeemer - typically $1000 for US bonds. Up until that point, bonds are freely tradeable and valued at whatever price the market deems appropriate.

It is important to properly define yield in the context of the bond market, because the definition differs somewhat from comparable investments. For a bond, two factors define the yield: the interest payments (coupon payments), and the spread between the purchase price and the face value of the bond.

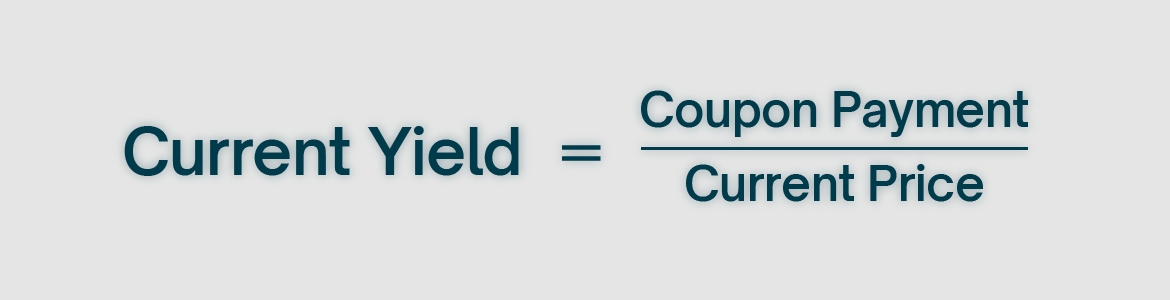

The simplest calculation, called the current yield, is as follows:

We can see from the above formula that the yield and the price are inversely correlated, meaning that if the price of the bond were to fall, then its yield would increase. Indeed, if an investor were to purchase a $1000 bond with a 5% coupon rate (meaning a $50 payment) at face value, the current yield would also be 5%. However, if an investor were to purchase the same bond at a discounted price of $800, then the current yield would increase to 6.25%. Important to keep in mind when reading financial news relating to falling/rising yields.

Another, and more perhaps more useful calculation, is the yield-to-maturity rate, which is the total return on investment made on the bond, assuming it is held until the maturity date. Such a calculation also assumes all coupon payments are reinvested at the same rate as the bond’s current rate, making it relatively difficult to calculate and certainly falling outside of the scope of this article. As we mentioned before, only longer-term bonds typically earn a coupon, meaning that the yield on shorter-term bonds is entirely defined by the spread between the purchase price and the face value.

For investors, the salient point about a bond is that it is a financial investment guaranteed by the government, and as such is considered the safest possible investment one could make. After all, if the government is no longer in a position to financially honour the bonds it issues, the investor will probably have much bigger problems to worry about than their portfolio.

For governments, bonds are an important part of how they fund their activities. By selling bonds, the country is essentially raising money, with the promise to pay back that money with interest further down the line. They are one of the primary tools a government uses to raise funds.

They also play another, essential role. Traditionally, a country would manipulate the strength of its currency by controlling the money supply. The more money in circulation, the weaker that money tends to be, and vice-versa. To increase the money supply, the central bank of that country would purchase government bonds, thereby injecting money into the system. Conversely, by selling those bonds, the central bank takes all that money back, reducing the supply. This is the mechanism by which a country could increase and decrease the money supply, and by doing so manipulate the relative strength of its currency.

The post-2008 modern financial era differs somewhat from this framework, but the buying and selling of bonds continues to be an important steering tool for monetary policy. To understand how, we need to look at something called the yield curve, which we will cover in part II of this article.

The backing vocalists at the Federal Reserve have stepped up to the mic, joining the hawkish chorus of voices calling to withhold interest rate cuts. Raphael Bostic chimed in on Thursday saying that inflation needs to draw closer to targets before bringing down borrowing costs. The Atlanta Fed President even went on to say that should inflation continue to veer off course then further rate hikes were not out of the question. New York Fed President John Williams echoed much of the same, saying there was no urgency to cut rates and that any decision to do so would be data-driven.

Despite a minor pullback on Wednesday, the DXY remains firmly above 106, putting pressure on other major currencies. Both the Euro and Cable are currently hovering around 6-month lows versus the Dollar, which is to say nothing of the Yen, which is now facing 35-year lows versus the greenback. The Bank of Japan has yet to establish a position on whether it will step in to defend the 155 level the currency pair is currently brushing up against.

Fears of higher interest rates for longer weighed heavily on US stocks this week. The Nasdaq Comp in particular is already down 3.5% since Monday, the DJI and S&P 500 also losing 0.55% and 2.2% respectively so far.

Uncharacteristically, gold has not set a new record high since Tuesday, content to consolidate under $2,400 an ounce for the time being. Oil prices are down this week following reports of another weekly build in crude inventories; Brent Crude is now back down to $86 a barrel, WTI down to $82.

US inflation figures have consistently come in hotter than expected since the start of the year, every data release increasing fears that interest rate cuts may be pushed further and further down the line. Such fears were all but confirmed on Tuesday during a press conference in Washington, during which Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell admitted that the inflation numbers seen so far have not instilled any degree of confidence to end restrictive monetary policy. Powell stated in no uncertain terms that “if higher inflation does persist, we can maintain the current level of restriction for as long as needed”. US jobless claims drop tomorrow, offering further clues about the state of the labour market.

The prospect of higher rates for longer continued to push the Dollar to even greater strengths early this week, the DXY briefly touching 106.5 yesterday. The hardest hit continued to be the Japanese Yen, with USDJPY already approaching the 155 level, up from 153 at the weekly open. There’s a growing sentiment that the Bank of Japan will be forced to step in at some point to protect the Yen, although there has been no official announcement as of yet. Japanese inflation figures are set to be released on Friday, which may offer some clarity to the situation.

Gold started the week strongly, gaining 1.7% on Monday and setting yet another record close at $2,382 an ounce. Despite some chop yesterday that level was maintained to close the day flat. Early trading this morning does not particularly suggest one direction or another.

Threats of escalation, drone strikes, calls for condemnation and restraint surrounding the Israeli-Iranian conflict all contributed to choppy trading conditions in gold markets over the weekend. Last Friday saw yet another record high for the precious metal, briefly reaching above $2,430 an ounce before a heavy retrace hammered prices back down to close the day 1.2% in the red. If a continuation of the downward pressure was expected this week, then so far it hasn’t materialised, as gold yet again continued to rise in early trading in Asia.

Markets at large appear to have accepted the fact that the Federal Reserve is not going to implement an interest rate cut any time soon, as evidenced by the continued strength of the Dollar. The DXY did just enough to earn a close above 106 on Friday, a level not seen since November last year. Higher than expected inflation numbers continued to be a lingering cause for concern last week, as did a stronger than expected labour market. The initial uptick in prices observed early in the year can no longer be safely attributed to seasonal deviations, as was originally hoped.

Looking forward to the week ahead, Monday will be dominated by American retail sales, followed on Tuesday by a variety of Chinese metrics, including retail sales of their own, industrial production, unemployment rate and GDP figures. Later on we have US jobless claims on Thursday, followed by more retail sales on Friday, this time from the UK. Economic calendar aside, barring any real moves to deescalate tensions in the Middle East, market participants may have to expect the unexpected again this coming week.

The fear surrounding the latest release of US inflation data turned out to be fully justified. We mentioned previously that many traders would be hoping the numbers would not beat expectations, but that is exactly what happened. The month-on-month and year-on-year core figures came in hotter than anticipated at 0.4% and 3.8% respectively. The data release preceded the FOMC minutes, which once again emphasised the need to tame inflation before any serious talk of monetary easing. Markets are now pricing in only two rate cuts this year as opposed to three.

The news sent the DXY flying straight over 105, up over one percent in its best day in a year. The move pushed USDJPY over 153 Yen, an exchange rate not seen since 1990. Other currencies also took a hammering versus the greenback, as did stocks. Adding confusion to the narrative, PPI figures dropped a day later on Thursday, which actually revealed lower than expected price rises, in direct opposition to the inflation data.

If American inflation figures came in too hot, then Chinese figures came in too cold. In a report on Thursday, inflation numbers for the world’s second largest economy came in far lower than expected at just 0.1%. Coupled with factory-gate prices continuing to decline, the release will no doubt contribute to growing concerns of deflationary pressure in the RMB.

Strength in the Dollar may have tempered the meteoric rise in gold on Wednesday, which saw bullion prices lose $18 an ounce, but the pullback did not last. Thursday saw yet another record high for the precious metal, this time reaching over $2,370 an ounce. By the looks of things, early Asian trading is pushing it higher still. Silver too, recently finding its footing, edged up to just under $29 an ounce during this morning’s trading session.

Part II:

How does the central bank change the interest rate?

In part I, we explained how central banks used interest rates to influence the strength of their respective currencies. But how do they do this? Changing interest rates is not quite as simple as fiddling with a dial to achieve the desired outcome, it requires a little more finesse than that. The exact mechanisms differ slightly from country to country, and are often tediously technical, so we’ll stick to basic principles whenever possible.

Let us first return to supply and demand. We mentioned previously that a lower interest rate is tied to a weaker currency and a higher money supply. If we exploit this correlation, then by changing the money supply we can manipulate the interest rate. As per the chart below, by moving the supply to the left or right of the demand curve, we decrease or increase rates.

Traditionally, modifying the money supply has been a major tool in a central bank’s arsenal for controlling interest rates. It does so via the buying and selling of government bonds. The exact nature of a bond falls outside of the scope of this article, but in the simplest terms, it is an IOU from the government. When the central bank buys a government bond, it takes that bond and pays cash into the system, increasing the available supply of money. Conversely, by selling that bond, it takes that cash back, reducing the available supply. The buying and selling of bonds therefore has a direct impact on the money supply.

The central bank has another tool at its disposal: it can tell regular banks how much money they must hold in reserve. This means that every bank has to hold a certain percentage of its deposits with the central bank. This limits the amount of money the bank has to lend out to its customers. Imagine a reserve rate of 10%. The bank has customer deposits worth one thousand Dollars. This means the bank is required to keep $100 with the central bank, while having $900 to use however it wishes, typically lending it out. Increasing or decreasing the reserve requirement therefore reduces or increases the amount of money in the system.

Finally, a central bank dictates the rate at which regular banks can borrow money from it. Although during normal operations banks usually borrow from each other, the central bank can act as a lender of last resort, setting a form of baseline interest rate for inter-bank lending. This in turn affects the rate at which those banks can profitably lend money to their clients, and to each other, once again indirectly affecting the money supply.

The above is important to understand from a historical perspective, but unfortunately, it explains economic conditions that have long since departed us. The tools previously described work in an environment of restricted monetary liquidity, or more concretely, they work when banks are forced to borrow money to cover their normal operations. This is no longer the case.

The financial crisis of 2008 changed everything. Following the crash, governments the world over enacted measures to inject liquidity into their economies in order to stimulate growth. Interest rates went straight to zero and central banks began injecting vast amounts of cash into their banking systems and mass purchasing assets - a process known as quantitative easing - hugely increasing the money supply. Supply and demand have flown out of the window because the fact of the matter is that the supply is now so large that manipulating it is utterly futile. Mathematically one may as well operate under the assumption that it is in fact infinite.

A new monetary era requires new monetary tools. How to influence banks when they don’t need to worry about limited reserves? The answer is to incentivise them. For the United States’ Federal Reserve, this is called interest on reserves. For the European Central Bank, it is called the deposit facility rate. The Bank of England simply calls it the bank rate, which previously meant something else. Different names but the purpose is the same: the central bank pays regular banks to deposit their cash reserves with them. For clarity, we will use the term “interest on reserves” from here on.

By earning interest on deposits held at the central bank, regular banks now have an extra option for their excess cash reserves. The bank can now lend money out to borrowers, earning interest payments from customers, or it can deposit that money at the central bank, earning interest on reserves. This creates a type of money marketplace where the various interest rates charged and offered by the bank never deviate too far from the rate fixed by the interest on reserves. The effective interest rate of a given currency therefore ties in closely with the interest on reserves awarded by the central bank.

One might expect the effective interest rate to be higher than the interest on reserves. After all, if a bank can earn more money from the central bank than it can by lending it out, then why bother taking the risk? The key here is that only banks can deposit their reserves at the central bank; nonbanks are not eligible for such a system. These nonbank lenders, lacking such an option, have an incentive to lend at any rate above zero, thereby lowering the overall effective interest rate. Banks are all too happy to borrow this money because they can arbitrage the spread between the lower interest repayments and the higher interest on reserves.

The 2008 crash prompted drastic changes in the way our monetary system works. Up until that point, banks operated within a framework of limited liquidity, forcing them to shore up their reserves and borrow enough to remain solvent. Following the crisis, the framework changed to one of extreme abundance, a completely different game. As recent as these changes are, whispers of another system of monetary governance are already emerging. How it will function is anyone’s guess, so let us once again anchor ourselves to the most fundamental definition of an interest rate: it is the price of using money. For as long as we retain any kind of debt-based monetary system, interest rates will remain the cornerstone of our financial world.

Advertencia de riesgos : Productos derivados del trading y productos potenciados poseen un nivel más alto de riesgo.

ABRIR CUENTA