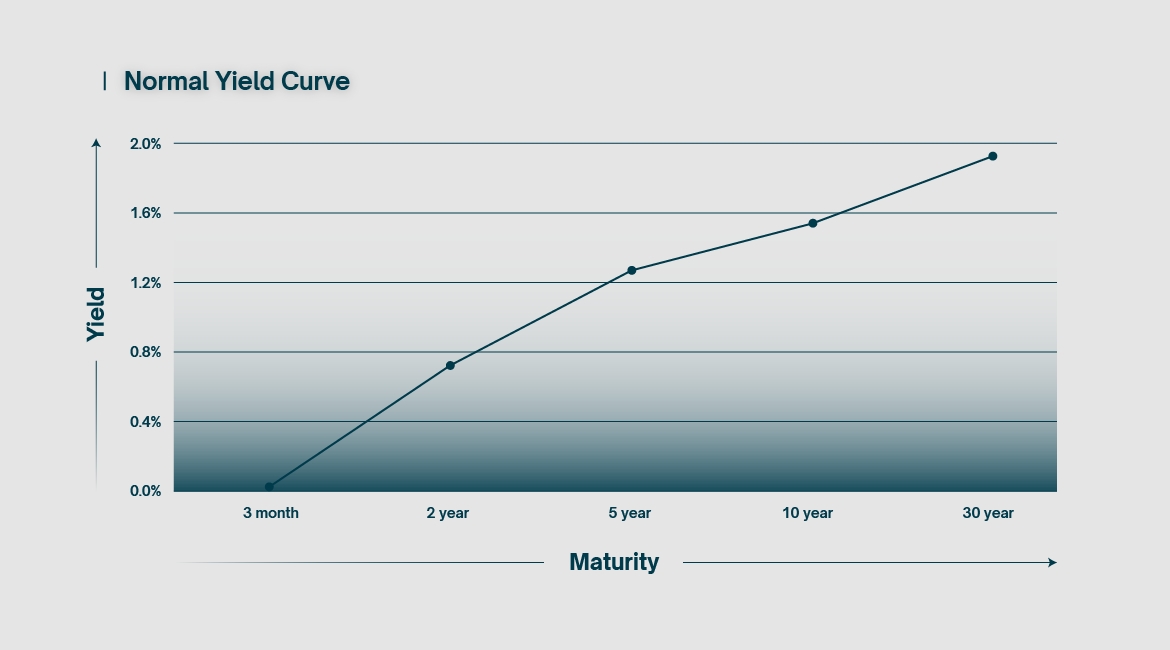

Simply put, the yield curve charts the yield earned on a

bond against its time to maturity. It is a snapshot in time and changes shape

regularly. Typically, the longer it takes a bond to mature, the better the

yield. This is hardly surprising; if an investor buys a ten-year bond as

opposed to a one-year bond, they should expect to receive a greater reward for

doing so, otherwise why bother? This creates an upward sloping chart,

considered a “normal” yield curve.

Due to market dynamics, yields on bonds are heavily tied to

interest rates at large. The shorter the time to maturity, the tighter the

correlation to the target interest rate set by the central bank of a nation.

Short-term bonds, typically under one year to maturity, are used as a benchmark

to price short-term borrowing and deposit rates. Longer-term bonds, typically a

minimum of ten years to maturity, reflect the longer-term costs of borrowing

and lending, such as for a mortgage.

The yield curve is a useful tool to quickly gauge interest

rates over time, but also offers a glimpse into the confidence that investors

have in a given economy. Put simply, if investors are losing confidence in the

nation’s economic performance, they will prefer to divert funds to safer but

lower-yielding, longer-term investments, such as bonds with 10+ year

maturities. Due to increased demand, these long-term bonds increase in price,

thereby lowering their yield (see part I for a more detailed explanation on

this). This pushes the right side of the curve downwards.

The opposite is also true. Confidence in the economy

translates to reduced demand in long-term bonds, because investors think they

can get a better return on investment in equities or other short-term

investments. Due to decreased demand, long-term bonds decrease in price,

thereby increasing their yield. This pushes the right side of the curve

upwards.

When reading financial news, one is likely to stumble upon

chatter relating to the ten-year US treasury yield. This financial instrument

is considered a particularly important benchmark for investors, given its

impact on long-term borrowing rates and its susceptibility to global

geopolitical sentiment. Variations in yield are reflective of variations in

demand, which in turn give a reliable indication of overall market sentiment.

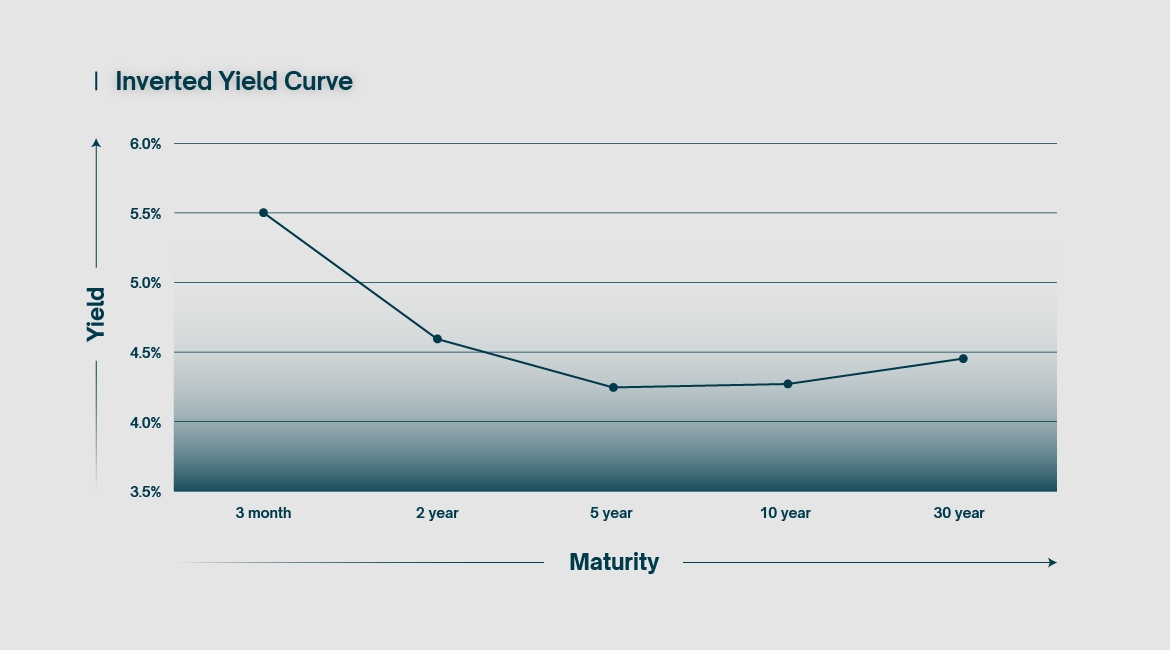

In rare cases, the bond market can experience something

called a yield curve inversion. This means that short-term interest rates

overtake long-term ones. We now have a chart that slopes downwards on at least

part of the curve. This is something that has occurred recently in some parts

of the world, due to central banks rapidly increasing interest rate targets to

contain inflation. One of the effects of such a policy was to drag short-term

bond yields above their longer-term counterparts.

On the surface this doesn’t make sense. How can investors

earn a better yield for a shorter commitment? Why would anyone bother buying

long-term bonds in such a situation? The answer is that those long-term rates

are locked in for longer. No one knows how long the short-term high yields will

last. An investor would have to constantly renew their position in the

short-term bond market to maintain the high yield, which could go down at any

time. This is called reinvestment risk and is a critical part of any trading

strategy for larger investment firms.

During times of high interest rates, short-term investments

are typically not as lucrative, due to a stronger currency and a restricted

money supply. As explained above, a lack of economic confidence tends to put

more buying pressure on longer-term investments, essentially reallocating money

from the present and pushing it into the future. The inverted yield curve

illustrates this phenomenon. So much so that an inversion of the yield curve

has been a historically consistent predictor of economic recession.

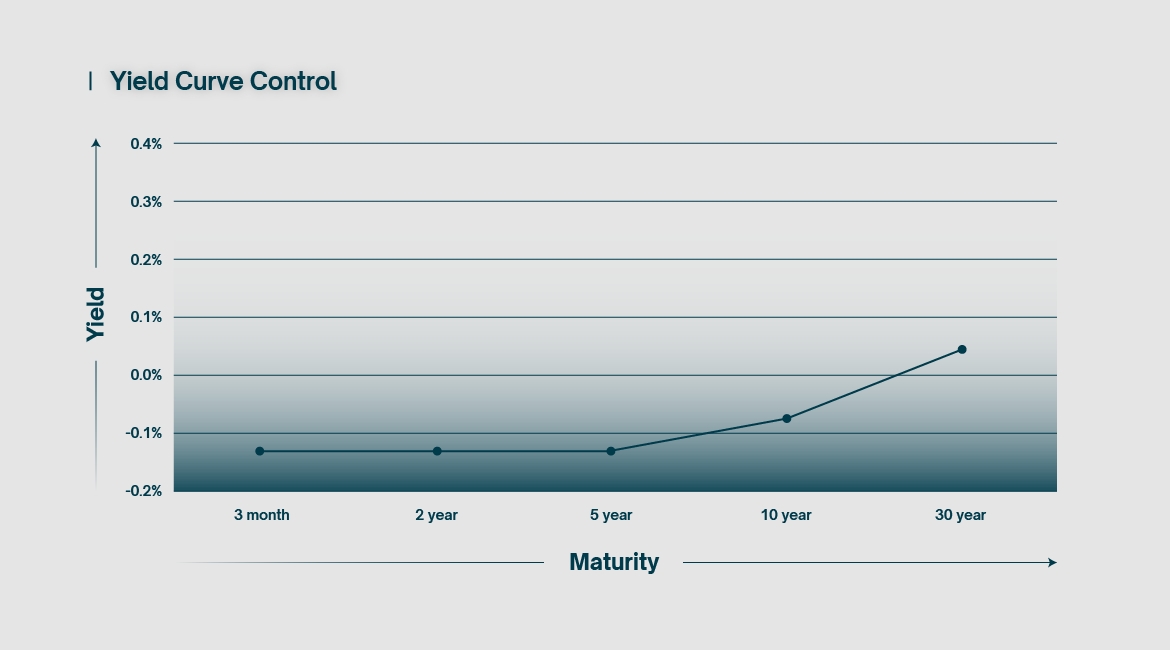

The first two charts result from somewhat natural market

dynamics. In contrast, the above chart is what happens when the central bank

takes full control of the bond market by employing a tool called yield curve

control. Yield curve control refers to the practice of a central bank

purchasing bonds of specific lengths with the express purpose of lowering their

respective yields to predefined targets. In essence, every central bank employs

some form of YCC, although they are typically targeting the short end of the

curve.

In the modern era, the term yield curve control is almost

exclusively used in the context of the Japanese economy, as a result of the

very specific conditions it has undergone since the 1990s. In an effort to drag

the nation out of decades of stagnation, the Bank of Japan sought to inject

some much-needed liquidity into its economy via the mass-purchasing of bonds

and other assets. Money was pumped into the Japanese banking system and

interest rates were pushed to zero and even below. Bond yields were crushed

across the board, suppressing the yield curve on all timeframes in an effort to

stimulate investment and growth in the beleaguered economy.

Unfortunately, this presented a particular problem for

longer-term interest rates and their influence on things like pensions and

mortgages. Many parties were understandably angry about the fact that long-term

bonds were no longer yielding any kind of return on investment. In an effort to

correct this, the Bank of Japan later allowed rates on higher timeframe bonds

to rise slightly, while keeping yields on short-term bonds strictly below zero.

Essentially, the yield curve was precisely tailored to specific targets, via

the controlled purchasing of bonds by the central bank, hence the term yield

curve control.

The use of yield curve control briefly gained more

international traction during the Covid years, but remains a relatively novel

and experimental tool. Even Japan has now abandoned the practice.

In

conclusion, the yield curve quite literally paints the monetary landscape at a

particular moment in time, offering insight into investor sentiment across a

large timespan. As useful a tool as this is, it remains at least partially open

to interpretation. Monetary policy has changed greatly in recent years, particularly

since the 2008 financial crisis. As the monetary frameworks within which our

economies operate continue to evolve, so too will our understanding of this

vital tool.

Risk Warning : Trading derivatives and leveraged products carries a high level of risk.

OPEN ACCOUNT